NEWS ROOM

ASG Lawyers honoured in The Best Lawyers in South Africa (2026) The directors and team at Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Inc. (ASG) are proud to announce that three of our lawyers have been recognised in The Best Lawyers in South Africa (2026) — an accolade based entirely on peer review and widely regarded as one of the most respected honours in the legal profession. Celebrating our recognised lawyers Craig Assheton-Smith , Director, has once again been acknowledged for his excellence in both Litigation and Insolvency and Reorganization Law. This marks his 15th consecutive year being recognised for Litigation — a testament to his unwavering commitment to clients, his strategic approach to complex disputes, and his respected standing among peers. Andrew Ginsberg, Director, has been recognised f or Arbitration and Mediation as well as Litigation , continuing a six-year streak of consecutive recognition in both categories. Andrew’s ability to navigate high-stakes disputes has earned him a reputation as a leading dispute resolution practitioner. Anne Venter, Director, has achieved her first recognition in The Best Lawyers in South Africa (2026) for Insolvency and Reorganization Law and Litigation. This honour highlights her growing impact and expertise in these challenging and dynamic areas of law. Recognition that reflects outstanding legal practice Each year, Best Lawyers identifies the top legal talent across jurisdictions through an exhaustive peer-review process. Lawyers are nominated and evaluated by their professional peers, ensuring that recognition is based solely on the quality of legal practice and ethical standards — not submissions or sponsorships. Learn more about the process at https://www.bestlawyers.com/article/legal-industry-secret-behind-best-lawyers/6602 This recognition reflects not only the individual achievements of Craig, Andrew, and Anne but also the collective strength of the ASG team. It is a reaffirmation of our continued focus on excellence, integrity, and client-centred service in every matter we undertake. Continuing the tradition of excellence At ASG, we view such recognition not as an endpoint, but as encouragement to continue setting the standard for litigation and dispute resolution in South Africa. We congratulate our colleagues on these well-deserved honours and thank our clients and peers for their ongoing trust and recognition.

Two lawyers at the boutique commercial and litigation firm, Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Inc, have yet again received recognition by being included in the 2024 edition of the Best Lawyers in South Africa™. Best Lawyers is respected by the profession, media, and the public as a reliable unbiased source of legal referrals. With lists in more than 75 countries, it is universally regarded as the definitive guide to legal excellence. Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Inc. is therefore pleased that two of its lawyers have been named consistently in the publication for several years now. In relation to their expertise in litigation, Craig Assheton-Smith has been included on the list since 2011 and Andrew Ginsberg since 2019. For the first time, in 2023, Andrew Ginsberg was also named to the arbitration and mediation listing. The firm has established a solid reputation over the past 12 years, delivering litigation and commercial services in highly complex voluminous matters for corporate clients and small and medium businesses. Lawyers on The Best Lawyers in South Africa list are divided by geographical region and practice areas. They are reviewed by their peers based on professional expertise and undergo an authentication process to make sure they are in current practice and good standing. For 2024, the two Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Inc. lawyers were acknowledged as follows: Craig Assheton-Smith – Litigation Andrew Ginsberg – Arbitration and Mediation and Litigation About Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Inc. ASG is a boutique commercial and litigation firm. Its attorneys are dedicated to successfully resolving clients’ commercial objective and disputes. They serve clients diligently with integrity and vision; clearly focused on finding solutions to resolve their legal disputes and helping them achieve success in their commercial and property transactions. The firm leaves nothing to chance when building successful strategies for its clients. Exercised with precision and combines with formidable relationships with Counsel, Correspondents and the Court Community the hands-on litigation tactics of its attorneys ensure impeccable service delivery to clients across a vast range of economic sectors and legal disputes. Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Inc. proudly offers the full array of corporate and commercial, dispute resolution, insolvency and business rescue, maritime, property and notarial legal services. The attorneys really listen to the clients, and by listening, understand their client’s businesses and strategies. If required, they research the commercial exigencies that clients face and align this accumulated intelligence with the law. Only then do they undertake to offer legal advice and strategic direction in achieving their commercial objectives. About Best Lawyers Best Lawyers is the oldest and most respected lawyer ranking service in the world. For more than 40 years, Best Lawyers has assisted those in need of legal services to identify the lawyers best qualified to represent them in distant jurisdictions or unfamiliar specialities. These awards are published in leading local, regional, and national publications across the globe.

The annual Best Lawyers® South Africa Edition were announced publicly today. Our congratulations to all our colleagues in the profession that were awarded Best Lawyer 2021, and especially to Craig and Andrew of Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Incorporated in the category Litigation. Craig has been nominated and awarded Best Lawyer in the field of litigation every year from 2011 to date, Andrew also being awarded Best Lawyer in the field of litigation for the past two years.

One of the most hotly debated issues in the short term insurance world at present, is the nature and extent of an insured’s cover under what are termed Infectious or Notifiable Disease extensions in certain indemnity insurance policies (the standard all risk policy that most businesses have in place). There have been at least three matters that have come or are currently being considered by our Courts regarding various Insurer’s liability under and in terms of these extensions. The first of these matters to be determined, which was ruled upon by the Western Cape High Court (per Le Grange J) in Cafe Chameleon CC v Guardrisk Insurance Co Limited is set to be heard on appeal by a full bench of the Supreme Court of Appeal on 23 November 2020. There are at least two other matters, yet undecided, which are currently before full benches of the High Court. The provision in question, relates to the business interruption section of the policy which is voluntary cover obtained to protect an insured against the business having to temporarily cease operation. In ordinary claims, such as those caused by fire for instance, an insured who has taken business interruption cover, would be covered against the physical damage caused by the fire itself as well as the business’s loss of profit for the period during which the business was forced to close whilst repairs were completed. Enter the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) and the path of destruction it has and continues to leave in its wake. National lock downs have been imposed globally including in South Africa restricting, and in most cases completely prohibiting, the operation of businesses deemed to be ‘non-essential’, imposing travel bans stifling the hospitality and tourism industry; and forcing restaurants, even under level 3 of Government’s risk adjusted strategy, to remain closed other than for delivery or take-away. Even under level 1, these businesses are required to operate at less than capacity with strict safety protocols being imposed. As a proprietor or shareholder of one of these businesses, one would not have been remiss in breathing a deep sigh of relief at reading that you are covered for interruption to your business caused by infectious disease, invariably assuming that interruptions caused by Covid-19, an infectious disease determined to be notifiable by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, would be covered. Unfortunately, as with most insurance cover, it is not quite as simple as that. Insurance companies are being faced with a flood of claims due to a risk that has not been seen on this scale for more than 100 years. A number of significant questions have been begged worldwide as to what duty insurers have to their clients to step up and assist, particularly when many of these clients face the stark reality of having to close their doors with the attendant impact, that this would have on the surrounding communities who rely on these companies for employment. Ironically, standard business interruption clauses usually exclude any cover should the insured be placed into liquidation. An irony which is likely not to be much appreciated by those facing the decision of throwing in the towel or waiting for a binding determination on the issue. On the other hand, the response from almost all (barring one or two Insurer), has predictably but quite unfortunately been a slew of very narrowly interpreted opinions which unsurprisingly have concluded that they are not liable in terms of the infectious disease clauses for the majority of disruptions caused by COVID19. Whilst the precise wording of the clause will be critical in interpreting the extent of cover, the four most prevalent defences to such claims, are: (1) the infectious disease clauses do not cover global pandemics but only localized outbreaks (despite no such express differentiation being made in the wording), based on the prevalence of words such as “an outbreak of which the competent local authority has stipulated shall be notified to them” , the argument being that if a global pandemic were envisaged the words would not be limited to a local authority; (2) it is not the virus that has caused the loss but the lockdown which is a risk not covered under the policy; (3) that if the business had to close because there was an outbreak within a defined radius, it had to be that specific incidence which caused the closure rather than a closure due to the general prevalence of the infection; and (4) Covid19 is not an identifiable disease as contemplated by the definition of same contained in the policy wording. The definition that appears in at least two similar policies is “Notifiable Disease shall mean illness sustained by any person resulting from any human infectious or human contagious disease an outbreak of which the competent local authority has stipulated shall be notified to them excluding Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) or an AIDS related condition”. Needless to say, it is difficult to engage with these arguments without at least some cynicism. The retort by one hotel group, supported by a team of arguably the finest legal minds in the Country, is that the particular insurer’s reliance on the abovementioned arguments are entirely indefensible, a view that seems to have been independently echoed by the Court in Café Chameleon and by Lord Justice Flaux and Mr Justice Butcher in a recent decision of the British High Court of Justice (Queens Bench). Many believe that insurer’s attempts to hide behind restrictive and narrow interpretations of these clauses is aimed at avoiding large scale payments rather than an earnest belief that the clause was not intended to cover Covid19 as a global pandemic. It is indeed unfortunate that insurers guided by their reinsurers have elected to hide behind narrow contractual interpretations rather than meaningfully contributing to the relief effort at a time when their financial strength is most desperately needed by their loyal customers. Whilst it must be said that certain insurers have offered relief in the form of ex gratia payments pending the final determination of the issue by the Courts, many see this as an attempt to save face under steadily mounting pressure from the public and private sector rather than a genuine attempt to assist. Perhaps now is the time for some introspection for the industry as a whole which rather than taking up the cudgel, seems to have adopted a far less magnanimous position. Whether this position is ultimately justifiable, will in all likelihood be a decision for the apex court in due course. This will however be cold comfort to the lodges, game reserves and hotels that are battling to keep their staff employed and their doors open.

One of the most hotly debated issues in the short term insurance world at present, is the nature and extent of an insured’s cover under what are termed Infectious or Notifiable Disease extensions in certain indemnity insurance policies (the standard all risk policy that most businesses have in place).

As knowledge workers, we regularly deal with a number of national and international disputes in a variety of jurisdictions. We are fortunate that, as a firm, we have consciously adopted a tech forward business strategy and have thus been using technology to work remotely for several years. Adapting to our unprecedented State imposed lock down, at least from a business and workflow perspective, has made little difference to our productivity. Whilst the firm has been business as usual, being locked down and not able to catch up with clients or friends has been challenging. These social gaps have been filled catching up in creative ways online via Zoom or Skype and always trying to uplift spirits with laughter and good cheer, not to forget the immense fear and sadness that this pandemic instills, but to ensure that we do not allow ourselves to become overwhelmed by its sheer magnitude. Although the South African courts are open, only prioritized matters under the COVID-19 regulations are being heard. This does not detract from the fact that many businesses need sound advice and guidance at this difficult time. We can help – from providing comprehensive legal opinions needed by large and small businesses to contractual defaults, and everything in between, we will assist you navigate through this crisis and beyond. Call us now on +27 21 424 7390.

The Western Cape High Court handed down judgment on 14 February 2019 in the matter of Watson & Another v Renasa Insurance Co Limited . The judgment dealt in part with the application of what has come to be known as the Reinstatement Value Conditions (“RVC”) clause, a common clause in many contemporary indemnity insurance policies (most notably, the Multimark III policy wording). This clause should not be confused with the Insurer’s right to reinstate (usually found in the general conditions to the policy) which affords the insurer the right to elect to either reinstate the property or effect payment in lieu thereof. The RVC clause affords the insured the election to be paid the cost of reinstating or repairing the damaged property with new property rather than accepting an indemnity payment calculated as being what it would have cost the insured to purchase similar used property immediately before the damage. The reinstatement value is often substantially higher than the indemnity value however, the RVC clause has a number of provisos including, the proviso that the work of reinstatement or repair “… must be commenced and carried out with reasonable dispatch, otherwise no payment, beyond the amount which would have been payable if these reinstatement value conditions had not been incorporated herein, shall be made ” as well as the proviso that “ until expenditure has been incurred by the insured in replacing and reinstating the property, the company shall not be liable for any payment in excess of the amount which would have been payable if these conditions had not been incorporated herein” . In the Watson matter, the argument arose before the Court that these provisos envisage that expensive print finishing machinery and premises needed to be secured by Mr Watson and monies expended thereon before he would be entitled to rely on the RVC clause. It was argued on behalf of Mr Watson, that he did not have the financial wherewithal, as a result of the delay caused by the insurer to do so and that it could not be expected of an impecunious insured to have to do so, without any undertaking from the insurer that payment would be forthcoming. The Court stated “ Clauses of this nature can give rise to difficulty and are open to potential abuse by an insurer who is less than bona fide. If no payment is made by an insurer at all, it places an impecunious (or relatively impecunious) claimant at a severe disadvantage when compared to similarly-placed insured parties, who are possessed of greater means. Such an impecunious insured would be required not merely to evidence a sincere intention to replace or reinstate the destroyed or damaged property, but would further be required to do so, absent any firm commitment by the insurer that it accepts liability for the resultant costs ”. Following the judgment in Grand Central Airport (Pty) Ltd v AIG South Africa Ltd the Court found that, in the context of the insurers argument that it should be the person that manages the insured’s reinstatement by being entitled to determine payment once and if compliance by the insured with the RVC clause has, in it’s view, taken place, the Court said “ To interpret these words as sanctioning the defendant’s conduct is a bridge too far. To my mind, it would offend against the legal convictions of the community to find that, in the present case, the defendant insurer should nonetheless be permitted to effectively slash the extent of its payment liability after having withheld the performance of its own indemnity payment obligation under the policy ”. Andrew Ginsberg of Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Inc., Mr Watson’s attorneys stated that “ this judgment should serve as a word of caution to insurers when the RVC clause is invoked by relatively impecunious insureds. If there is no argument as to liability, this judgment seems to be precedent that, at the very least, the indemnity value should be paid which will give the insured the necessary capital to commence reinstatement” .

Team Assheton-Smith’s hard bitten animal lovers won out in the choice of how to give back for Mandela day and we spent our 67 minutes for Mandela on 18 July 2015 working for the Domestic Animal Rescue Group (DARG). Everyone buckled down to making treats and toys for the animals at DARG. Assheton-Smith Incorporated represents the Court appointed facilitator for DARG which has entailed a number of court applications which are ongoing, brought in order to clarify DARG’s legal rights to continue to occupy the land upon which it operates and in order to recover funds that were unaccounted for. It was our pleasure to once more help with the fantastic work the facilitator and his team are doing to not only put things right at DARG but to amplify and preserve an amazing organisation that really does make an enormous difference to abused, abandoned and diseased animals, restoring them and finding good homes for them.

Team Assheton-Smith’s hard bitten animal lovers won out in the choice of how to give back for Mandela day and we spent our 67 minutes for Mandela on 18 July 2015 working for the Domestic Animal Rescue Group (DARG). Everyone buckled down to making treats and toys for the animals at DARG. Assheton-Smith Incorporated represents the Court appointed facilitator for DARG which has entailed a number of court applications which are ongoing, brought in order to clarify DARG’s legal rights to continue to occupy the land upon which it operates and in order to recover funds that were unaccounted for. It was our pleasure to once more help with the fantastic work the facilitator and his team are doing to not only put things right at DARG but to amplify and preserve an amazing organisation that really does make an enormous difference to abused, abandoned and diseased animals, restoring them and finding good homes for them.

As an ongoing part of our growth and development, Team Assheton-Smith gathered in Riebeeck Kasteel in early February 2015 to share ideas and workshop team processes, facilitated by the Yellowbaobab Institute of Leadership. Everyone was highly inspired and a lot of fun was had by all finding out how we all fit together and how to harness our strengths and mitigate our weaknesses. At the end of the weekend we celebrated the new Assheton-Smith Incorporated’s third birthday in style!

Craig Assheton-Smith was once again selected to be listed on the Best Lawyers awards for 2015 in the specialist category Litigation. Craig has received nominations and selections from various independent bodies such as Chambers and Partners, Legal 500 and Best Lawyers over the past decade, ranking him among not only South Africa’s top legal minds but also in the world. The attached article on Craig was published in the Business Day on 30 October 2014 together with the announcement of the awards.

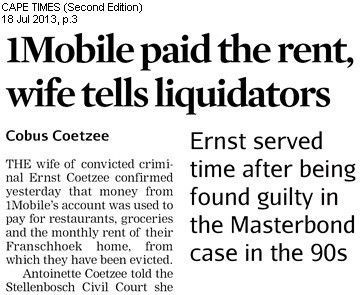

Masterbond-man erken dat hy al weer bedrieg Translation: Masterbond man once again admits that he committed fraud Yesterday one of the masterminds behind the Masterbond case admitted to committing fraud and not paying tax. Yesterday, Ernst Coetzee appeared in the Stellenbosch Civil Court where there was an enquiry held in relation to the affairs of 1Mobile. The Company, 1 Mobile, which was registered under the name of Red Sunset Trading 14 (Pty) Ltd, was liquidated in October 2012. Coetzee, who served a prison sentence after being found guilty of fraud in the Masterbond case in the 1990’s, was sequestrated. He was one of the managers of 1Mobile. A total of 94 investors invested money with 1Mobile for the purchasing of cellphone terminals which one would be able to purchase airtime from. The concept of the Company was that the investors would pay R6000.00 per terminal which terminal would be installed, managed and maintained by 1Mobile. 1Mobile promised a return of 40% per year (on the R6000.00), if an investor was to conclude a joint venture agreement with 1Mobile, such investor would be able to earn 50% on the turnover which the investor’s terminal would generate. The terminal is a small machine, just bigger than a regular office telephone landline, which can be installed in any shop where airtime for a cellphone can be purchased. According to court documents approximately R84 000 000.00 flowed through the Company’s bank statements. According to Ryno Engelbrecht, the liquidator of the Company, it still remains to be determined exactly how much money investors lost, since the forensic audit has not yet been completed. Shortly after Red Sunset Trading 14 was liquidated, a handful of investors requested that an enquiry be conducted into the affairs of the Company. Attorney Craig Assheton-Smith, who conducted the enquiry, put various aspects of the venture to Coetzee. He wanted to know, inter alia, about Dirk Joubert a director of 1Mobile, and if he was aware that the Company financed various payments of a personal nature to Mr Coetzee. Such payments included payments in relation to Coetzee’s wife- and son’s motor vehicles, their cell phone contracts, DSTV and groceries. Coetzee advised that Joubert had been aware of this. Assheton-Smith further examined Coetzee as to if he ever paid any tax on the aforesaid payments. “No”, Coetzee answered. He further admitted that the Company also paid for the rental; of a farm near Franschoek (were Coetzee and his family lived) but that these payments were in arrears because of the fact that the Company went into liquidation. “The landlord had to get an eviction order to remove you from the premises because you did not want to move”, Assheton-Smith said. Coetzee admitted same. Finally Assheton-Smith questioned him if any of the promises made to one of the investors, Theo Oosthysen, were fulfilled by the Company. Coetzee admitted that not all the monies Oosthyzen had invested were allocated to buying terminals.

The Supreme Court of Appeal recently dismissed an appeal that was brought in respect of a judgment of Rabie J in the High Court, Pretoria. The judgment of Rabie J dismissed an application brought against Senwesbel Limited and Senwes Limited by the Treacle Fund II Trust to set aside certain share transactions. Craig Assheton-Smith said, “The success in this matter is attributable to attention to detail, sound knowledge of the legal principles and hard work by all members of the legal team. The judgments by Rabie J and by the Supreme Court of Appeal are well reasoned and based upon well-established legal principles.” The judgment can be viewed by following this link: http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZASCA/2013/35.html

We would like to congratulate Anne Venter, and wish her the best for her upcoming Application for Admission as an Attorney, set for Friday, 7 June 2013. With aspirations of growing her own practice within Assheton-Smith Incorporated, the vast experience and tutorage she is receiving under the leadership of Craig Assheton-Smith is setting the foundation for her future career and success as an attorney. “We are a small select team which affords me the opportunity to be involved in all aspects of matters from inception. I have gained insight as to how crucial it is to formulate a strategy before commencing with a matter and never to underestimate our opponents nor assume anything, always double, if not triple check your facts,” says Anne Venter of her experience within the firm to date. She credits her parents and role models, Margriet and Johann Venter for her strong values and ethics, and her tenacity and commitment; these values are apparent in Anne’s work ethic. Professional background: Admitted to the degree B.Comm.Law in 2007 at the University of Stellenbosch. Admitted to the degree LL.B in 2009 at the University of Stellenbosch. Attended and completed the Association of Law Societies of South Africa’s School for Legal Practice from 5 July 2011 until 24 November 2011 in Cape Town. Passed the Attorney’s Admission Examinations in 2012. Application for Admission as an Attorney is set down for Friday, 7 June 2013.

News & Updates

RECENT POSTS

ASG Lawyers honoured in The Best Lawyers in South Africa (2026) The directors and team at Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Inc. (ASG) are proud to announce that three of our lawyers have been recognised in The Best Lawyers in South Africa (2026) — an accolade based entirely on peer review and widely regarded as one of the most respected honours in the legal profession. Celebrating our recognised lawyers Craig Assheton-Smith , Director, has once again been acknowledged for his excellence in both Litigation and Insolvency and Reorganization Law. This marks his 15th consecutive year being recognised for Litigation — a testament to his unwavering commitment to clients, his strategic approach to complex disputes, and his respected standing among peers. Andrew Ginsberg, Director, has been recognised f or Arbitration and Mediation as well as Litigation , continuing a six-year streak of consecutive recognition in both categories. Andrew’s ability to navigate high-stakes disputes has earned him a reputation as a leading dispute resolution practitioner. Anne Venter, Director, has achieved her first recognition in The Best Lawyers in South Africa (2026) for Insolvency and Reorganization Law and Litigation. This honour highlights her growing impact and expertise in these challenging and dynamic areas of law. Recognition that reflects outstanding legal practice Each year, Best Lawyers identifies the top legal talent across jurisdictions through an exhaustive peer-review process. Lawyers are nominated and evaluated by their professional peers, ensuring that recognition is based solely on the quality of legal practice and ethical standards — not submissions or sponsorships. Learn more about the process at https://www.bestlawyers.com/article/legal-industry-secret-behind-best-lawyers/6602 This recognition reflects not only the individual achievements of Craig, Andrew, and Anne but also the collective strength of the ASG team. It is a reaffirmation of our continued focus on excellence, integrity, and client-centred service in every matter we undertake. Continuing the tradition of excellence At ASG, we view such recognition not as an endpoint, but as encouragement to continue setting the standard for litigation and dispute resolution in South Africa. We congratulate our colleagues on these well-deserved honours and thank our clients and peers for their ongoing trust and recognition.

Two lawyers at the boutique commercial and litigation firm, Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Inc, have yet again received recognition by being included in the 2024 edition of the Best Lawyers in South Africa™. Best Lawyers is respected by the profession, media, and the public as a reliable unbiased source of legal referrals. With lists in more than 75 countries, it is universally regarded as the definitive guide to legal excellence. Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Inc. is therefore pleased that two of its lawyers have been named consistently in the publication for several years now. In relation to their expertise in litigation, Craig Assheton-Smith has been included on the list since 2011 and Andrew Ginsberg since 2019. For the first time, in 2023, Andrew Ginsberg was also named to the arbitration and mediation listing. The firm has established a solid reputation over the past 12 years, delivering litigation and commercial services in highly complex voluminous matters for corporate clients and small and medium businesses. Lawyers on The Best Lawyers in South Africa list are divided by geographical region and practice areas. They are reviewed by their peers based on professional expertise and undergo an authentication process to make sure they are in current practice and good standing. For 2024, the two Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Inc. lawyers were acknowledged as follows: Craig Assheton-Smith – Litigation Andrew Ginsberg – Arbitration and Mediation and Litigation About Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Inc. ASG is a boutique commercial and litigation firm. Its attorneys are dedicated to successfully resolving clients’ commercial objective and disputes. They serve clients diligently with integrity and vision; clearly focused on finding solutions to resolve their legal disputes and helping them achieve success in their commercial and property transactions. The firm leaves nothing to chance when building successful strategies for its clients. Exercised with precision and combines with formidable relationships with Counsel, Correspondents and the Court Community the hands-on litigation tactics of its attorneys ensure impeccable service delivery to clients across a vast range of economic sectors and legal disputes. Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Inc. proudly offers the full array of corporate and commercial, dispute resolution, insolvency and business rescue, maritime, property and notarial legal services. The attorneys really listen to the clients, and by listening, understand their client’s businesses and strategies. If required, they research the commercial exigencies that clients face and align this accumulated intelligence with the law. Only then do they undertake to offer legal advice and strategic direction in achieving their commercial objectives. About Best Lawyers Best Lawyers is the oldest and most respected lawyer ranking service in the world. For more than 40 years, Best Lawyers has assisted those in need of legal services to identify the lawyers best qualified to represent them in distant jurisdictions or unfamiliar specialities. These awards are published in leading local, regional, and national publications across the globe.

The annual Best Lawyers® South Africa Edition were announced publicly today. Our congratulations to all our colleagues in the profession that were awarded Best Lawyer 2021, and especially to Craig and Andrew of Assheton-Smith Ginsberg Incorporated in the category Litigation. Craig has been nominated and awarded Best Lawyer in the field of litigation every year from 2011 to date, Andrew also being awarded Best Lawyer in the field of litigation for the past two years.

One of the most hotly debated issues in the short term insurance world at present, is the nature and extent of an insured’s cover under what are termed Infectious or Notifiable Disease extensions in certain indemnity insurance policies (the standard all risk policy that most businesses have in place). There have been at least three matters that have come or are currently being considered by our Courts regarding various Insurer’s liability under and in terms of these extensions. The first of these matters to be determined, which was ruled upon by the Western Cape High Court (per Le Grange J) in Cafe Chameleon CC v Guardrisk Insurance Co Limited is set to be heard on appeal by a full bench of the Supreme Court of Appeal on 23 November 2020. There are at least two other matters, yet undecided, which are currently before full benches of the High Court. The provision in question, relates to the business interruption section of the policy which is voluntary cover obtained to protect an insured against the business having to temporarily cease operation. In ordinary claims, such as those caused by fire for instance, an insured who has taken business interruption cover, would be covered against the physical damage caused by the fire itself as well as the business’s loss of profit for the period during which the business was forced to close whilst repairs were completed. Enter the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) and the path of destruction it has and continues to leave in its wake. National lock downs have been imposed globally including in South Africa restricting, and in most cases completely prohibiting, the operation of businesses deemed to be ‘non-essential’, imposing travel bans stifling the hospitality and tourism industry; and forcing restaurants, even under level 3 of Government’s risk adjusted strategy, to remain closed other than for delivery or take-away. Even under level 1, these businesses are required to operate at less than capacity with strict safety protocols being imposed. As a proprietor or shareholder of one of these businesses, one would not have been remiss in breathing a deep sigh of relief at reading that you are covered for interruption to your business caused by infectious disease, invariably assuming that interruptions caused by Covid-19, an infectious disease determined to be notifiable by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, would be covered. Unfortunately, as with most insurance cover, it is not quite as simple as that. Insurance companies are being faced with a flood of claims due to a risk that has not been seen on this scale for more than 100 years. A number of significant questions have been begged worldwide as to what duty insurers have to their clients to step up and assist, particularly when many of these clients face the stark reality of having to close their doors with the attendant impact, that this would have on the surrounding communities who rely on these companies for employment. Ironically, standard business interruption clauses usually exclude any cover should the insured be placed into liquidation. An irony which is likely not to be much appreciated by those facing the decision of throwing in the towel or waiting for a binding determination on the issue. On the other hand, the response from almost all (barring one or two Insurer), has predictably but quite unfortunately been a slew of very narrowly interpreted opinions which unsurprisingly have concluded that they are not liable in terms of the infectious disease clauses for the majority of disruptions caused by COVID19. Whilst the precise wording of the clause will be critical in interpreting the extent of cover, the four most prevalent defences to such claims, are: (1) the infectious disease clauses do not cover global pandemics but only localized outbreaks (despite no such express differentiation being made in the wording), based on the prevalence of words such as “an outbreak of which the competent local authority has stipulated shall be notified to them” , the argument being that if a global pandemic were envisaged the words would not be limited to a local authority; (2) it is not the virus that has caused the loss but the lockdown which is a risk not covered under the policy; (3) that if the business had to close because there was an outbreak within a defined radius, it had to be that specific incidence which caused the closure rather than a closure due to the general prevalence of the infection; and (4) Covid19 is not an identifiable disease as contemplated by the definition of same contained in the policy wording. The definition that appears in at least two similar policies is “Notifiable Disease shall mean illness sustained by any person resulting from any human infectious or human contagious disease an outbreak of which the competent local authority has stipulated shall be notified to them excluding Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) or an AIDS related condition”. Needless to say, it is difficult to engage with these arguments without at least some cynicism. The retort by one hotel group, supported by a team of arguably the finest legal minds in the Country, is that the particular insurer’s reliance on the abovementioned arguments are entirely indefensible, a view that seems to have been independently echoed by the Court in Café Chameleon and by Lord Justice Flaux and Mr Justice Butcher in a recent decision of the British High Court of Justice (Queens Bench). Many believe that insurer’s attempts to hide behind restrictive and narrow interpretations of these clauses is aimed at avoiding large scale payments rather than an earnest belief that the clause was not intended to cover Covid19 as a global pandemic. It is indeed unfortunate that insurers guided by their reinsurers have elected to hide behind narrow contractual interpretations rather than meaningfully contributing to the relief effort at a time when their financial strength is most desperately needed by their loyal customers. Whilst it must be said that certain insurers have offered relief in the form of ex gratia payments pending the final determination of the issue by the Courts, many see this as an attempt to save face under steadily mounting pressure from the public and private sector rather than a genuine attempt to assist. Perhaps now is the time for some introspection for the industry as a whole which rather than taking up the cudgel, seems to have adopted a far less magnanimous position. Whether this position is ultimately justifiable, will in all likelihood be a decision for the apex court in due course. This will however be cold comfort to the lodges, game reserves and hotels that are battling to keep their staff employed and their doors open.